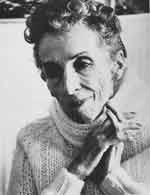

Karen

Blixen (Isak Dinesen)

from Seven Gothic Tales

What is man, when you come to think upon him, but a minutely set, ingenious machine for turning, with infinite artfulness, the red wine of Shiraz into urine?

If,

in planting a coffee tree, you bend the taproot, that tree will start,

after a little time, to put out a multitude of small delicate roots near

the surface. That tree will never thrive, nor bear fruit, but it will

flower more richly than the others.

Those fine roots are the dreams of the tree. As it puts them out, it need

no longer think of its bent taproot. It keeps alive by them— a little,

not very long. Or you can say that it dies by them, if you like. For really,

dreaming is the well-mannered people's way of committing suicide.

If all your life you had been tacking up against the winds and the currents, and suddenly, for once, you were taken on board a ship which went, as we do tonight, with a strong tide and before a following wind, you would undoubtedly be much impressed with the power of that ship. You would be wrong; and yet in a way you would also be right, for the power of the waters and the winds might be said rightly to belong to the ship, since she had managed, alone amongst all vessels, to ally herself with them.

![]() N

a full-moon night of 1863 a dhow was on its way from Lamu to Zanzibar,

following the coast about a mile out. She carried full sails before the

monsoon, and had in her a freight of ivory and rhino-horn. This last is

highly valued as an aphrodisiac, and traders come for it to Zanzibar from

as far as China. But besides these cargoes the dhow also held a secret

load, which was about to stir and raise great forces, and of which the

slumbering countries which she passed did not dream.

N

a full-moon night of 1863 a dhow was on its way from Lamu to Zanzibar,

following the coast about a mile out. She carried full sails before the

monsoon, and had in her a freight of ivory and rhino-horn. This last is

highly valued as an aphrodisiac, and traders come for it to Zanzibar from

as far as China. But besides these cargoes the dhow also held a secret

load, which was about to stir and raise great forces, and of which the

slumbering countries which she passed did not dream.

This still night was bewildering in its deep silence and peace, as if something had happened to the world; as if the soul of it had been, by some magic, turned upside down. The free monsoon came from far places, and the sea wandered on under its sway, on her long journey, in the face of the dim luminous moon. But the brightness of the moon upon the water was so clear that it seemed as if all the light in the world were in reality radiating from the sea, to be reflected in the skies. The waves looked solid, as if one might safely have walked upon them, while it was into the vertiginous sky that one might sink and fall, into the turbulent and unfathomable depths of silvery worlds, of bright silver or dull and tarnished silver, forever silver reflected within silver, moving and changing, towering up, slowly and weightless.

The two

slaves in the prow were still like statues, their bodies, naked to the

waist in the hot night, iron-gray like the sea where the moon was not

shining on it, so that only the clear dark shades running along their

backs and limbs marked out their forms against the vast plane. The red

cap of one of them glowed dull, like a plum, in the moonlight. But one

corner of the sail, catching the light, glinted like the while belly of

a dead fish. The air was like that of a hothouse, and so damp that all

the planks and ropes of the boat were sweating a salt dew. The heavy waters

sang and murmured along the bow and stern.

On the after deck a small lantern was hung up, and three people were grouped round it.

The first of them was young Said Ben Ahamed, the son of young water-carrier looked up at the window too, and kept standing there, gazing at the maiden. So the Sultan became very sad, and he had the virgin and the young man buried alive together, in a marble chest broad enough to make a marriage bed, under a palm tree of his garden, and seating himself below the same tree he wondered at many things, and at how he was never to have his heart's desire, and he had a young boy to play the flute to him. That was the tale you heard once."

"Yes,

but better told then," said Lincoln.

"It was that," said Mira, "and the world could not do without

Mira then. People love to be frightened. The great princes, fed up with

the sweets of life, wished to have their blood stirred again. The honest

ladies, to whom nothing ever happened, longed to tremble in their beds

just for once. The dancers were inspired to a lighter pace by tales of

flight and pursuit. Ah, how the world loved me in those days! Then I was

handsome, round-cheeked. I drank noble wine, wore gold-embroidered clothes

and amber, and had incense burned in my rooms."

"But how has this change come upon you?" asked Lincoln.

"Alas!" said Mira, sinking back into his former quiet manner,

"as I have lived I have lost the capacity of fear. When you know

what things are really like, you can make no poems about them. When you

have had talk with ghosts and connections with the devils you are, in

the end, more afraid of your creditors than of them; and when you have

been made a cuckold you are no longer nervous about cuckoldry. I have

become too familiar with life; it can no longer delude me into believing

that one thing is much worse than the other. The day and the dark, an

enemy and a friend—I know them to be about the same. How can you

make others afraid when you have forgotten fear yourself? I once had a

really tragic tale, a great tale, full of agony, immensely popular, of

a young man who in the end had his nose and his ears cut off. Now I could

frighten no one with it, if I wanted to, for now I know that to be without

them is not so very much worse than to have them. This is why you see

me here, skin and bone, and dressed in old rags, the follower of Said

in prison and poverty, instead of keeping near the thrones of the mighty,

flourishing and flattered, as was young Mira Jama."

"But could you not, Mira," Lincoln asked, "make a terrible

tale about poverty and unpopularity?"

"No," said the story-teller proudly, "that is not the sort

of story which Mira Jama tells."

"Well, yes, alas," said Lincoln, turning around on his side,

"what is life, Mira, when you come to think upon it, but a most excellent,

accurately set, infinitely complicated machine for turning fat playful

puppies into old mangy blind dogs, and proud war horses into skinny nags,

and succulent young boys, to whom the world holds great delights and terrors,

into old weak men, with running eyes, who drink ground rhino-horn?"

"Oh, Lincoln Forsner," said the noseless story-teller, "what

is man, when you come to think upon him, but a minutely set, ingenious

machine for turning, with infinite artfulness, the red wine of Shiraz

into urine? You may even ask which is the more intense craving and pleasure:

to drink or to make water. But in the meantime, what has been done? A

song has been composed, a kiss taken, a slanderer slain, a prophet begotten,

a righteous judgment given, a joke made. The world drank in the young

story-teller Mira. He went to its head, he ran in its veins, he made it

glow with warmth and color. Now I am on my way down a little; the effect

has worn off. The world will soon be equally pleased to piss me out again,

and I do not know but that I am pressing on a little myself. But the tales

which I made—they shall last."

"What do you do in the meantime to keep so good a face toward it,

in this urgency of life to rid itself of you?" Lincoln asked.

"I dream," said Mira.

"Dream?" said Lincoln.

"Yes, by the grace of God," said Mira, "every night, as

soon as I sleep I dream. And in my dreams I still know fear. Things are

terrible to me there. In my dreams I sometimes carry with me something

infinitely dear and precious, such as I know well enough that no real

things be, and there it seems to me that I must keep this thing against

some dreadful danger, such as there are none in the real world. And it

also seems to me that I shall be struck down and annihilated if I lose

it, though I know well that you are not, in the world of the daytime,

struck down and annihilated, whatever you lose. In my dreams the dark

is filled with indescribable horrors, but there are also sometimes flights

and pursuits of a heavenly delight."

He sat for a while in silence.

"But what particularly pleases me about dreams," he went on,

"is this: that there the world creates itself around me without any

effort on my part. Here, now, if I want to go to Gazi, I have to bargain

for a boat, and to buy and pack my provisions, to tack up against the

wind, and even to make my hands sore by rowing. And then, when I get to

Gazi, what am I to do there? Of that also I must think. But in my dreams

I find myself walking up a long row of stone steps which lead from the

sea. These steps I have not seen before, yet I feel that to climb them

is a great happiness, and that they will take me to something highly enjoyable.

Or I find myself hunting in a long row of low hills, and I have got people

with me with bows and arrows, and dogs in leads. But what I am to hunt,

or why I have gone there, I do not know. One time I came into a room from

a balcony, in the very early morning, and upon the stone floor stood a

woman's two little sandals, and at the same moment I thought: they are

hers. And at that my heart overflowed with pleasure, rocked in ease. But

I had taken no trouble. I had had no expense to get the woman. And at

other times I have been aware that outside the door was a big black man,

very black, who meant to kill me; but still I had done nothing to make

him my enemy, and I shall just wait for the dream itself to inform me

how to escape from him, for in myself I cannot find out how to do it.

The air in my dreams, and particularly since I have been in prison with

Said, is always very high, and I generally see myself as a very small

figure in a great landscape, or in a big house. In all this a young man

would not take any pleasure at all; but to me, now, it holds such delight

as does making water when you have finished with wine."

"I do not know about it, Mira; I hardly ever dream," said Lincoln.

"Oh, Lincoln, live forever," said old Mira. "You dream

indeed more than I do myself. Do I not know the dreamers when I meet them?

You dream awake and walking about. You will do nothing yourself to choose

your own ways: you let the world form itself around you, and then you

open your eyes to see where you will find yourself. This journey of yours,

tonight, is a dream of yours. You let the waves of fate wash you about,

and then you will open your eyes tomorrow to find out where you are."

"To see your pretty face," said Lincoln.

"You know, Tembu," said Mira suddenly, after a pause, "that

if, in planting a coffee tree, you bend the taproot, that tree will start,

after a little time, to put out a multitude of small delicate roots near

the surface. That tree will never thrive, nor bear fruit, but it will

flower more richly than the others.

"Those fine roots are the dreams of the tree. As it puts them out,

it need no longer think of its bent taproot. It keeps alive by them—

a little, not very long. Or you can say that it dies by them, if you like.

For really, dreaming is the well-mannered people's way of committing suicide.

"If you want to go to sleep at night, Lincoln, you must not think,

as people tell you, of a long row of sheep or camels passing through a

gate, for they go in one direction, and your thoughts will go along with

them. You should think instead of a deep well. In the bottom of that well,

just in the middle of it, there comes up a spring of water, which runs

out in little streamlets to all possible sides, like the rays of a star.

If you can make your thoughts run out with that water, not in one direction,

but equally to all sides, you will fall asleep. If you can make your heart

do it thoroughly enough, as the coffee tree does it with the little surface

roots, you will die."

"So that is the matter with me, you think: that I want to forget

my taproot?" asked Lincoln.

"Yes," said Mira, "it must be that. Unless it be that,

like many of your countrymen, you never had much of it."

"Unless it be that," said Lincoln.

They sailed on for a little while in silence. A slave took up a flute

and played a few notes on it, to try it.

"Why does not Said speak a word to us?" Lincoln asked Mira.

Said lifted his eyes a little and smiled, but did not speak.

"Because he thinks," said Mira. "This conversation of ours

seems to him very insipid."

"What is he thinking of?" asked Lincoln.

Mira thought for a little. "Well," he said, "there are

only two courses of thought at all seemly to a person of any intelligence.

The one is: What am I to do this next moment?—or tonight, or tomorrow?

And the other: What did God mean by creating the world, the sea, and the

desert, the horse, the winds, woman, amber, fishes, wine? Said thinks

of the one or the other."

"Perhaps he is dreaming," said Lincoln.

"No," said Mira after a moment, "not Said. He does not

know how to dream yet. The world is just drinking him in. He is going

to its head and into its blood. He means to drive the pulsation of its

heart. He is not dreaming, but perhaps he is praying to God. By the time

when you have finished praying to God—that is when you put out your

surface roots; that is when you begin to dream. Said tonight may be praying

to God, throwing his prayer at the Lord with such energy as that with

which the Angel shall, upon the last day, throw at the world the note

of his trump, with such energy as that with which the elephant copulates.

Said says to God: 'Let me be all the world.'

"He says," Mira went on after a minute, "I shall show no

mercy, and I ask for none. But that is where Said is mistaken. He will

be showing mercy before he has done with all of us."

"Do you ever dream of the same place twice?" asked Lincoln after

a time.

"Yes, yes," said Mira. "That is a great favor of God's,

a great delight to the soul of the dreamer. I come back, after a long

time, in my dream, to the place of an old dream, and my heart melts with

delight."

They sailed on for some time, and no one said anything. Then Lincoln suddenly

changed his position, sat up, and made himself comfortable. He spat out

on the deck the last of his Morungu, dived into a pocket, and rolled himself

a cigarette.

"I will tell you a tale tonight, Mira," he said, "since

you have none. You have reminded me of long-gone things. Many good stories

have come from your part of the world to ours, and when I was a child

I enjoyed them very much. Now I will tell this one, for the pleasure of

your ears, Mira, and for the heart of Said, to whom my tale may prove

useful. It all goes to teach you how I was, twenty years ago, taught,

as you say, Mira, to dream, and of the woman who taught me. It happened

just as I tell it to you. But as to names and places, and conditions in

the countries in which it all took place, and which may seem very strange

to you, I will give you no explanation. You must take in whatever you

can, and leave the rest outside. It is not a bad thing in a tale that

you understand only half of it."

Twenty

years ago, when I was a young man of twenty-three, I sat one winter night

in the room of a hotel, amongst mountains, with snow, storm, great clouds

and a wild moon outside.

Now the continent of Europe, of which you have heard, consists of two

parts, the one of which is more pleasant than the other, and these two

are separated by a high and steep mountain chain. You cannot cross it

except in a few places where the formation of the mountains is a little

less hostile than elsewhere, and where roads have been made, with much

trouble, to take you over them. Such a place there was near the hotel

where I was staying. A road that would admit pedestrians, horses and mules,

and even coaches had been cut in the rocks, and on the top of the pass,

where, from laboriously climbing upwards, cursing your fate, you begin

to descend, soon to feel the sweet air caressing your face and lungs,

a brotherhood of holy men have built a great house for the refreshment

of travelers. I was on my way from the North, where things were cold and

dead, to the blue and voluptuous South. The hotel was my last station

before the steep journey to the top of the pass, which I meant to undertake

on the next day. It was a little early in the season yet to travel this

way at all. There were only a few people on the road as yet, and higher

up in the mountains the snow was lying deep.

To the world I looked a pretty, rich, and gay young man, on his way from

one pleasure to another, and providing himself, on the way, with the best

of everything. But in truth I was just being whirled about, forward and

backward, by my aching heart, a poor fool out on a wild-goose chase after

a woman.

Yes, after a woman, Mira, if you believe it or not. I had already been

searching for her in a variety of places. In fact, so hopeless was my

pursuit of her that I should most certainly have given it up if it had

been at all within my power to do so. But my own soul, Mira, my dear,

was in the breast of this woman.

And she was not a girl of my own age. She was many years older than I.

Of her life I knew nothing except what was painful to me to swallow, and,

what was the worst of the business, I had no reason to believe that she

would be at all pleased should I ever contrive to find her.

The whole thing had come about like this: My father was a very rich man

in England, the owner of large factories and of a pleasant estate in the

country, a man with a big family and an enormous working capacity. He

read the Bible much—our Holy Book—and had come to feel himself

God's one substitute on earth. Indeed, I do not know if he was capable

of making any distinction between his fear of God and his self-esteem.

It was his duty, he thought, to turn the chaotic world into a universe

of order, and to see that all things were made useful—which, to him,

meant making them useful to him himself. Within his own nature I know

of two things only which he could not control: he had, against his own

principles, a strong love of music, particularly of Italian opera music;

and he sometimes could not sleep at night. Later on I was told by my aunt,

his sister, who much disliked him, that he had, as a young man in the

West Indies, driven to suicide, or actually killed, a man. Perhaps this

was what kept him awake. I and my twin sister were much younger than our

other brothers and sisters. What flea had bitten my father that he should

beget two more children when he had got through most of his trouble with

the rest of us, I do not know. At the day of judgment I shall ask him

for an explanation. I have sometimes thought that it was really the ghost

of the West Indian gentleman which had been after him.

My father was not pleased with anything which I did. In the end I think

that I became a carking care to him, for had I not been of his own manufacture

he would have been pleased to see me come to a bad end. Now I felt that

I was ever, as My Son Lincoln, being drawn, hammered and battered into

all sorts of shapes, in order to be made useful, between one o'clock and

three of the night. During these hours I myself generally had a pretty

heated and noisy time, for I had become an officer in a smart regiment

of the army, and there, to keep up my prestige amongst the sons of the

oldest families of the land, spent much of the money, time, and wit which

my father reckoned to be really and rightly his.

At about this time a neighbor of ours died, and left a young widow. She

was pretty and rich, and had been unhappily married, and in her trials

had consoled herself with a sentimental friendship with my twin sister,

who was so like me that if I dressed up in her clothes nobody would know

the one of us from, the other. Therefore my father now thought that this

lady might consent to marry me, and lift the burden of me from his shoulders

onto hers. This prospect suited me as well as anything that I at that

time expected from life. The only thing for which I asked my father was

his consent to let me travel on the continent of Europe during the lady's

year of mourning. In those days I had various strong inclinations, for

wine, gambling and cockfighting, and the society of gypsies, together

with a passion for theological discussion which I had inherited from my

father himself—all of which my father thought I had better rid myself

of before I married the widow, or, at least, which I had better not let

her contemplate at too close quarters while she could still change her

mind. As my father knew me to be quick and ardent in love affairs, I think

that he also feared that I might seduce my fiancee into too close a relation,

profiting by our neighborhood in the country, and, perhaps, by my likeness

to my sister. For all these reasons the old man agreed that I should go

traveling for nine months, in the company of an old schoolfellow of his,

who had lived on his charity and whom he was pleased to turn in this way

to some sort of use.

This man, however, I soon managed to rid myself of, for when we came to

Rome he took up the study of the mysteries of the ancient Priapean cult

of Lampsacus and I enjoyed myself very well.

But in the fourth month of my year of grace, it happened to me that I

fell in love with a woman within a brothel of Rome. I had gone there,

on an evening, with a party of theologians. It was thus not a dashing

place. Where people with lots of money went to amuse themselves, neither

was it a murky house frequented by artists or robbers. It was just a middling

respectable establishment. I remember the narrow street in which it stood,

and the many smells which met therein. If ever I were to smell them again,

I should feel that I had come home. To this woman I owe it that I have

ever understood, and still remember, the meaning of such words as tears,

heart, longing, stars, which you poets make use of. Yes, as to stars in

particular, Mira, there was much about her that reminded one of a star.

There was the difference between her and other women that there is between

an overcast and a starry sky. Perhaps you too have met in the course of

your life women of that sort, who are self-luminous and shine in the dark,

who are phosphorescent, like touchwood.

As, upon the next day, I woke up in my hotel in Rome, I remember that

I had a great fright. I thought: I was drunk last night; my head has played

a trick on me. There are no such women. At this I grew hot and cold all

over. But again I thought, lying in my bed: I could not possibly, all

on my own, have invented such a person as this woman. Why, only our greatest

poet could have done that. I could never have imagined a woman with so

much life in her, and that great strength. I got up and went straight

back to her house, and there I found her again, such indeed as I remembered

her.

Later on I learned that the extraordinary impression of great strength

which she gave me was somehow false after all; she had not all the strength

that she showed. I will tell you what it was like:

If all your life you had been tacking up against the winds and the currents,

and suddenly, for once, you were taken on board a ship which went, as

we do tonight, with a strong tide and before a following wind, you would

undoubtedly be much impressed with the power of that ship. You would be

wrong; and yet in a way you would also be right, for the power of the

waters and the winds might be said rightly to belong to the ship, since

she had managed, alone amongst all vessels, to ally herself with them.

Thus had I, all my life, under my father's aegis, been taught to tack

up against all the winds and currents of life. In the arms of this woman

I felt myself in accord with them all, lifted and borne on by life itself.

This, to my mind then, was due to her great strength. And still, at that

time I did not know at all to what extent she had allied herself with

all the currents and winds of life.

After this first night we were always together. I have never been able

to get anything out of the orthodox love affairs of my country, which

begin in the drawing-room with banalities, flatteries and giggles, and

go through touches of hands and feet, to finish up in what is generally

held to be a climax, in the bed. This love affair of mine in Rome, which

began in the bed, helped on by wine and much noisy music, and which grew

into a kind of courtship and friendship hitherto unknown to me, was the

only one that I have ever liked. After a while I often took her out with

me for the whole day, or for a whole day and night. I bought a small carriage

and a horse, with which we went about in Rome and in the Cpagna, as far

as Frascati and Nemi. We supped in the little inns, and in the early mornings

we often stopped on the road and let the horse graze on the roadside,

while we ourselves sat on the ground, drank a bottle of fresh, sour, red

wine, ate raisins and almonds, and looked up at the many birds of prey

which circled over the great plain, and whose shadows, upon the short

grass, would run alongside our carriage. Once in a village there was a

festival, with Chinese lamps around a fountain in the clear evening. We

watched it from a balcony. Several times, also, we went as far as the

seaside. It was all in the month of September, a good month in Rome. The

world begins to be brown, but the air is as clear as hill water, and it

is strange that it is full of larks, and that here they sing at that time

of the year.

Olalla was very pleased with all this. She had a great love for Italy,

and much knowledge of good food and wine. At times she would dress up,

as gay as a rainbow in cashmeres and plumes, as a prince's mistress, and

there never was a lady in England to beat her then; but at other times

she would wear the linen hood of the Italian women, and dance in the villages

in the manner of the country. Then a stronger or more graceful dancer

was not to be found, although she liked even better to sit with me and

watch them dance. She was extraordinarily alive to all impressions. Wherever

we went together she would observe many more things than I did, though

I have been a good sportsman all my life. But at the same time there never

seemed to be to her much difference between joy and pain, or between sad

and pleasant things. They were all equally welcome to her, as if in her

heart she knew them to be the same.

One afternoon we were on our way back to Rome, about sunset, and Olalla,

bareheaded, was driving the horse and whipping him into a gallop. The

breeze then blew her long dark curls away from her face, and showed me

again a long scar from a burn, which, like a little white snake, ran from

her left ear to her collar bone. I asked her, as I had done before, how

she had come to be so badly burned. She would not answer, but instead

began to talk of all the great prelates and merchants of Rome who were

in love with her, until I said, laughing, that she had no heart. Over

this she was silent for a little while, still going at full speed, the

strong sunlight straight in our faces.

"Oh, yes," she said at last, "I have a heart. But it is

buried in the garden of a little white villa near Milan."

"Forever?" I asked.

"Yes, forever," she said, "for it is the most lovely place."

"What is there," I asked her, oppressed by jealousy, "in

a little white villa of Milan to keep your heart there forever?"

"I do not know," she said. "There will not be much now,

since nobody is weeding the garden or tuning the piano. There may be strangers

living there now. But there is moonlight there, when the moon is up, and

the souls of dead people."

She often spoke in this vague whimsical way, and she was so graceful,

gentle, and somehow humble in it that it always charmed me. She was very

keen to please, and would take much trouble about it, though not as a

servant who becomes rigid by his fear of displeasing, but like somebody

very rich, heaping benefactions upon you out of a horn of plenty. Like

a tame lioness, strong of tooth and claw, insinuating herself into your

favor. Sometimes she seemed to me like a child, and then again old, like

those aqueducts, built a thousand years ago, which stand over the Campagna

and throw their long shadows on the ground, their majestic, ancient, and

cracked walls shining like amber in the sun. I felt like a new, dull thing

in the world, a silly little boy beside her then. And always there was

that about her which made me feel her so much stronger than myself. Had

I known for certain that she could fly, and might have flown away from

me and from the earth whenever she choose to, it would have given me the

same feeling, I believe.

It was not till the end of September that I began to think of the future.

I saw then that I could not possibly live without Olalla. If I tried to

go away from her, my heart, I thought, would run back to her as water

will run downhill. So I thought that I must marry her, and make her come

to England with me.

If when I asked her she had made the slightest objection, I should not

have been so much upset by her behavior later on. But she said at once

that she would come. She was more caressing, more full of sweetness toward

me from that time than she had ever been before, and we would talk of

our life in England, and of everything there, and laugh over it together.

I told her of my father, and how he had always been an enthusiast about

the Italian opera, which was the best thing that I could find to say of

him. I knew, in talking to her about all this, that I should never again

be bored in England.

It was about then that I was for the first time struck by the appearance,

whenever I went near Olalla, of a figure of a man that I had never seen

before. The first few times I did not think of it, but after our sixth

or seventh meeting he began to occupy my thoughts and to make me curiously

ill at ease. He was a Jew of fifty or sixty years, slightly built, very

richly dressed, with diamonds on his hands, and with the manners of a

fine old man of the world. He was of a pale complexion and had very dark

eyes.

I never

saw him with her, or in the house, but I ran into him when I went there,

or came away, so that he seemed to me to circle around her, like the moon

around the earth. There must have been something extraordinary about him

from the beginning, or I should not have had the idea, which now filled

my head, that he had some power over Olalla and was an evil spirit in

her life. In the end I took so much interest in him that I made my Italian

valet inquire about him at the hotel where he was living, and so learned

that he was a fabulously rich Jew of Holland, and that his name was Marcus

Cocoza.

I came to wonder so much about what such a man could have to do in the

street of Olalla's house, and why he thus appeared and again disappeared,

that in the end, half against my will—for I was afraid of what she

might tell me—I asked her if she knew him. She put two fingers under

my chin and lifted it up. "Have you not noted about me, Carissime,"

she asked me, "that I have no shadow? Once upon a time I sold my

shadow to the devil, for a little heart-ease, a little fun. That man whom

you have seen outside—with your usual penetration you will easily

guess him to be no other than this shadow of mine, with which I have no

longer anything to do. The devil sometimes allows it to walk about. It

then naturally tries to come back and lay itself at my feet, as it used

to do. But I will on no account allow it to do so. Why, the devil might

reclaim the whole bargain, did I permit it! Be you at ease about him,

my little star."

She was, I thought, in her own way obviously speaking the truth for once.

As she spoke I realized it: she had no shadow. There was nothing black

or sad in her nearness, and the dark shades of care, regret, ambition,

or fear, which seem to be inseparable from all human beings—even

from me myself, although in those days I was a fairly careless boy—had

been exiled from her presence. So I just kissed her, saying that we would

leave her shadow in the street and pull down the blind.

It was about this time, too, that I began to have a strange feeling, that

I have come to know since, and which I then innocently mistook for happiness.

It seemed to me, wherever I went, that the world around me was losing

its weight and was slowly beginning to flow upwards, a world of light

only, of no solidity whatever. Nothing seemed massive any longer. The

Castel San Angelo was entirely a castle in the air, and I felt that I

might lift the very Basilica of St. Peter between my two fingers. Nor

was I afraid of being run over by a carriage in the streets, so conscious

was I that the coach and the horses would have no more weight in them

than if they had been cut out of paper. I felt extremely happy, if slightly

light-headed, under the faith, and took it as a foreboding of a greater

happiness to come, a sort of apotheosis. The universe, and I myself with

it, I thought, was on the wing, on the way to the seventh heaven. Now

I know well enough what it means: it is the beginning of a final farewell;

it is the cock crowing. Since then, on my travels, I have known a country

or a circle of people to have taken on that same weightless aspect. In

one way I was right. The world around me was indeed on the wing, going

upwards. It was only me myself, who, being too heavy for the flight, was

to be left behind, in complete desolation.

I was occupied with the thought of a letter that I must write to my father,

to tell him that I could not marry the widow, when I was informed that

one of my brothers, who was an officer in the navy, was at Naples with

his ship. I reflected that it might be better to give him the letter to

carry, and told Olalla that I should have to go to Naples for a couple

of days. I asked her if she would be likely to see the old Jew while I

was away, but she assured me that she would neither see him nor speak

to him.

I did not get on quite well with my brother. When I talked to him, I saw

for the first time how my plans for the future would appear to the eyes

of others, and it made me feel very ill at ease. For while I still held

their views to be idiotic and inhuman, I was yet, for the first time since

I had met Olalla, reminded of the dead and clammy atmosphere of my former

world and my home. However, I gave my letter to my brother, and asked

him to plead my cause with my father as well as he could, and I hastened

to return to Rome.

When I came back there I found that Olalla had gone. At first they told

me, in the house where she had been, that she had died suddenly from fever.

This made me deadly ill and nearly drove me mad for three days. But I

soon found out that it could not possibly be so, and then I went to every

inhabitant of the house, imploring and threatening them to tell me all.

I now realized that I ought to have taken her away from the place before

I went to Naples— although what would it have helped me if she herself

had meant to leave me? A strange superstition made me connect her disappearance

with the Jew, and in a last interview with the madama of the house I seized

her by the throat, told her that I knew all, and promised her that I would

strangle her if she did not tell me the truth. In her terror the old woman

confessed: Yes, it had been he. Olalla had left the house one day and

had not come back. The next day a pale old Jewish gentleman with very

dark eyes had appeared at the house, had settled Olalla's debts and paid

a sum to the madama to raise no trouble. She had not seen the two together.

"And where have they gone?" I cried, sick because I had not

had an outlet for my despair in killing off the old yellow female. That

she could not tell me, but on second thought she believed that she had

heard the Jew mention to his servant the name of a town called Basel.

To Basel I then proceeded, but people who have not themselves tried it

can have no idea of the difficulties you have in trying to find, in a

strange town, a person whose name you do not know.

My search was made more difficult by the fact that I did not know at all

in what station of life I was to seek Olalla. If she had gone with the

Jew she might be a great lady by now, whom I should meet in her own carriage.

But why had the Jew left her in the house where I had found her in Rome?

He might do the same thing now, for some reason unknown to me. I therefore

searched all the houses of ill renown in Basel, of which there are more

than one would think, for Basel is the town in Europe which stands up

most severely for the sanctity of marriage. But I found no trace of her.

I then bethought me of Amsterdam, where I should have, at least, the name

of Cocoza to go by. I did indeed find, in Amsterdam, the fine old house

of the Jew, and learned about him that he was the richest man of the place,

and that his family had traded in diamonds for three hundred years. But

he himself, I was told, was always traveling. It was thought that he was

now in Jerusalem. I ran, from Amsterdam, upon various false tracks which

took me to many countries. This maddening journey of mine went on for

five months. In the end I made up my mind to go to Jerusalem, and I was

on my way back to Italy, to take ship at Genoa, and these things were

all running through my mind when I was sitting, as I have told you, at

the Hotel of Andermatt, waiting to cross the pass upon the following day.

On the previous day I had found a letter from my father, which had been

following at my heels for some months, being sent after me from one place

to another. My father wrote to me:

"I am now able to look upon your conduct with calm and understanding.

This I owe to the perusal of a collection of family papers, to which I

have during the three last months given much of my time and attention.

From the study of these papers it has become clear to me that a highly

remarkable fate lies, and for the last two hundred years has lain, upon

our family.

"We are, as a family, only so much better than others because we

have always had amongst us one individual who has carried all the weakness

and vice of his generation. The faults which normally would have been

divided up among a whole lot of people have been gathered together upon

the head of one of them only, and we others have in this way come to be

what we have been, and are.

"In

going through our papers I can no longer have any doubt of this fact.

I have been able to trace the one particular chosen delinquent through

seven generations, beginning with our great-aunt Elizabeth, into whose

behavior I do not want here to go. I shall only quote the examples of

my uncles Henry and Ambrose, who in their days without any doubt . . ."

Here followed various names and facts for the support of my father's theory.

He then continued:

"I do not know whether it would not be more of a fatal blow than

of a blessing to our name and family should this strange condition ever

cease to be. It might do away with much trouble and anxiety, but it might

also lead to the family becoming no better than other people.

"As to you, you have so perseveringly declined to follow my command

or advice that I feel I have reason to believe you the chosen victim of

your generation. You have refused to make, by your example, virtue attractive

and the reward of good conduct obvious. I have now reached, in my relation

to you, a sufficiently philosophical outlook to give you my blessing in

the completion of a career which may make filial disobedience, weakness,

and vice a usefully repugnant and deterring example to your generation

of our family."

I never saw my father again. But from my former tutor, whom, many years

later, I happened to meet again in Smyrna, in melancholy circumstances,

I heard of him. My father had so far reconciled himself to the situation

as to marry my young widow himself. They had a son, and him he christened

Lincoln. But whether he did so because after all he had liked me better

than I had known, or with the purpose of removing any unpleasant sensations

which might present themselves to him between one and three o'clock of

a night, in connection with the thought of his son Lincoln, I cannot tell.

I had read his letter twice, and was taking it from my pocket to read

it again to pass the time, when, looking up, I saw two young men come

into the dining-room of the hotel from the cold night outside. One of

them I knew, and I thought that if he caught sight of me he would come

and sit down with me, which he did, so that the three of us spent the

rest of the night together.

The first of these two nicely dressed and well-mannered young gentlemen

was a boy of a noble family of Coburg, whom, a year before, I had known

in England, where he was sent to study parliamentary procedure, since

he meant to become a diplomat, and also to study horse-breeding, which

was the livelihood of his people. His name was Friederich Hohenemser,

but he was, in looks and manners, so like a dog I had once owned and which

was named Pilot, that I used to call him that. He was a tall and fair,

handsome, young man.

But since it will please you, Mira, to hear your own ingenious parable

made use of, I am going to tell you of him that he was a person whom life

would on no account consent to gulp down. He had himself a burning craving

to be swallowed by life, and on every occasion would try to force himself

down her throat, but she just as stubbornly refused him. She might, from

time to time, just to imbue him with an illusion, sip in a little of him,

though never a good full draught; but even on these occasions she would

vomit him up again. What it was about him which thus made her stomach

rise, I cannot quite tell you; only I know this: that all people who came

near him had, somehow, the same feeling about him, that, while they had

nothing against him, here was a fellow with whom they could do nothing

at all. In this way he was, mentally, in the state of a very young embryo.

It probably takes a certain amount of cunning, or luck, in a man to get

himself established as an embryo. My friend Pilot had never got beyond

that. His condition was often felt by himself, I believe, as very alarming;

and so indeed it was. His blue eyes at times gave out a most painful reflection

of the hopeless struggle for existence which went on inside him. If he

ever found in himself any original taste at all, he made the most of it.

Thus he would go on talking of his preference for one wine over another,

as if he meant to impress such a precious finding deeply upon you. A philosopher,

about whom I was taught in school and whom you would have liked, Mira,

has said: "I think; consequently I am." In this way did my friend

Pilot repeat to himself and to the world: "I prefer Moselle to Rhenish

wine; consequently I exist." Or, if he enjoyed a show or a game,

he would dwell upon it the whole evening, telling you: "That sort

of thing amuses me." But he had no imagination, and was, besides,

very honest. He could invent nothing for himself, but was left to describe

such preferences as he really found in his own mind, which were always

preciously few. Probably it was, altogether, his lack of imagination which

prevented him from existing. For if you will create, as you know, Mira,

you must first imagine, and as he could not imagine what Friederich Hohenemser

was to be like, he failed to produce any Friederich Hohenemser at all.

I had named him, I have told you, after a dog of mine, which had so much

the same sort of disposition—never having the slightest idea of what

he wanted to do, or had to do—that I finished up by shooting him.

The God of Friederich Hohenemser was more forbearing to him in the end.

With all this, Pilot did not get on badly in society, which, I suppose,

demands but a minimum of existence from its members, on the continent

of Europe. He was, besides, a rich young man, pink and white, with a pair

of vigorous calves—about all of which he was not a little vain—and

he was even thought by elderly ladies to be a very model of a youth. He

liked me, and was pleased at having made such a definite impression on

me that I had given him a nickname. A person, he thought, has given me

a nickname. Consequently I exist.

As he now came up to me I noticed that a change had come upon him. He

had come to life; there was a shine about him. Thus did the dog Pilot

shine and wag his tail upon the rare occasions on which he hoped to have

proved that he did really exist. It might have been, in the boy, the effect

of his new friendship with the young gentleman who accompanied him. In

any case he would be sure, I felt, to play out his ace to me in the course

of the evening. I sighed. I would have given much, on that night, for

the company of a really good dog. I thought regretfully of my old dogs

in England.

He presented his friend to me as Baron Guildenstern of Sweden. I had not

had the pleasure of their company for ten minutes before I had been informed

by both of them that the Baron in his own country held the reputation

of a great seducer of women. This made me meditate—although all the

time my intercourse with other people was carried on only upon the surface

of my mind—on what kind of women they have in Sweden. The ladies

who have done me the honor of letting me seduce them have, all of them,

insisted upon deciding themselves which was to be the central point in

the picture. I have liked them for it, for therein lay what was to me

the variety of an otherwise monotonous performance. But in the case of

the Baron it was clear that the point of gravity had always been entirely

with him. You would suppose him to be of an unenthusiastic nature, even

while he was talking of the beauties whom he had pursued, but you would

not find him lacking in enthusiasm when he had once turned your eyes toward

what he wanted you really to admire. It appeared from his talk that all

his ladies had been of exactly the same kind, and that kind of woman I

have never met. With himself so absolutely the hero of each single exploit,

I wondered why he should have taken so much trouble—and he was obviously

prepared to go to any length of trouble in these affairs—to obtain,

time after time, a repetition of exactly the same trick. To begin with

I was, being a young man myself, highly impressed by such a superabundance

of appetite.

Still I got, after a while, from his conversation, which was very lively

and became more so after we had emptied a few bottles together, the key

to the existence of the young Swede, which lay in the single word "competition."

Life, to him, was a competition in which he must needs shine beyond the

other entrants. I had myself been fairly keen for competition as a boy,

but even while I had been still at school I had lost my sense of it, and

by this time, unless a thing was in itself to my taste, I thought it silly

to exert myself about it just because it happened to be to the taste of

others. Not so this Swedish Baron. Nothing in the whole world was in itself

good or bad to him. He was waiting for a cue, and a scent to follow, from

other people, and to find out from them what things they held precious,

in order to outshine them in the pursuit of such things, or to bereave

them of them. When he was left alone he was lost. In this way he became

more dependent upon others than Pilot himself, and probably he shunned

solitude as the very devil. His past life, I found from his talk, he saw

as a row of triumphs over a row of rivals, and as nothing else whatever,

although he was a little older than I. Neither in his rivals nor in his

victims had he any interest at all. He had in him neither admiration nor

pity, no feeling that was not either envy or contempt.

Yet he was no fool. On the contrary, I should say that he was a very shrewd

person. He had adopted in life the manner of a good, plain, outspoken

fellow who is a little unpolished but easily forgiven on account of his

open, simple mind. With that he had an attentive, lurking glance, and

spied on you, when you least expected it, in order to get from you a valuation

of things, so as to be able to defraud you of them. As he was without

the nerves which make ordinary people feel the strain of things, he had

without doubt an extraordinary strength and stamina, and was held by himself

and by others to be a giant in comparison with those who have imagination

or compassion in them.

The two got on very well together, Pilot being flattered into existence

by the cute young Swede—I have got, Pilot thought, a friend who is

a terrible seducer of women; consequently I exist—and the Baron quite

pleased to have outshone all former friends of the rich young German,

and to be admired by him. They would really rather have been without me.

But they were drawn magnetically toward me, Pilot to show off his friend

to me, and the Baron hot on the track of something which I might value

or want, and which he might win or trick from me.

I was so bored, after a while, with the conversation of the Baron that

I turned my attention to Pilot—a thing rarely done by anyone —and

as soon as he got the chance he began to reveal to me the great happenings

in his life.

"You might not care to be seen in my company, Lincoln," he said,

"if you knew all. I shall not be out of danger till I am out of Switzerland.

The walls have ears in a country of so much political unrest." He

waited to watch the effect of his words, then went on: "I come from

Lucerne."

Now I knew that there had been a fight in that town, but it had never

occurred to me that Pilot might have been in it.

"It was hot there," he said. Poor Pilot! In his little, bashfully

smiling mouth the very truth sounded badly invented. The Baron, I am sure,

would have made a whole chain of lies come out with such aplomb that his

audience would not for a moment have doubted them. "I shot a man

in the barricade fight on the third of March," said Pilot.

I knew that there had been a fight in the streets between, on the one

side, the parties in power, and particularly the partisans of the priests,

and on the other, the common people in rebellion. "You did?"

I asked, with a deep pang of envy because he had been in a fight. "You

shot a rebel?" For Pilot had always been to me a figure of high respectability

and small intellect. I took it for granted that he had sided with the

priests, and this at least I did not envy him.

Pilot shook his head proudly and secretively. After a moment he said,

"I shot the chaplain of the Bishop of St. Gallen."

The newspapers had been full of this murder, and the murderer had been

searched for everywhere. I naturally became interested to know how the

great deed had fallen to Pilot, and made him tell me his tale from the

beginning. The Baron, bored by the recount of somebody else's martial

exploits, sat without listening, drinking and watching the people as they

went in and out.

"When I went away from Coburg," said Pilot, "I meant to

stay in Lucerne for three weeks with my uncle De Watteville. As I was

about to depart, all the elegant ladies of the place, one after the other,

begged me to bring her back from Lucerne a bonnet from a milliner whom

they called Madame Lola. This woman, they assured me, was famous from

one end of Europe to the other. Ladies from the great courts and capitals

came to her for their bonnets, and never in the history of millinery had

there been such a genius. I was naturally not averse to doing the ladies

of my native town a service, so I went off, my pockets bulging with little

silk patterns, and even, will you believe it, with little locks of hair

for Madame Lola to match her bonnets to. Still, in Lucerne, where the

air was filled with political discussions, I forgot all about Madame Lola

until one night, when I was dining with a party of high officials and

politicians, I suddenly drew out, with my handkerchief, a little slip

of rose-colored satin, and had to furnish my explanation. To my surprise

the whole conversation immediately turned to the milliner. The married

men, at least, and all the clericals, all knew about her. It was true,

said the Bishop of St. Gallen, who was present, that the woman was a genius.

The slightest touch of her hand, like a magic wand, created miracles of

art and elegance, and the great ladies of St, Petersburg and Madrid, and

of Rome itself, made pilgrimages to the milliner's shop. But she was more

than that. She was suspected of being a conspirator of the first water,

who made use of her atelier as a meeting place for the most dangerous

revolutionists. And in this capacity, also, she was a genius, a Circe,

moving and organizing things with her little hands, and the roughest of

her partisans would have died for her.

"They all warned me so strongly against her that naturally the first

thing which I did on the following day was to go to her house, in the

street which had been pointed out to me. On that occasion I found her

only a highly intelligent and agreeable woman. She took all my orders,

and talked to me of my journey and even of my character and career. A

red-haired young man came in while I was there, and went out again, who

looked much like a revolutionist, but to whom she paid but little attention.

"While she was completing all these bonnets for me, the atmosphere

of Lucerne was darkening more and more; a thunderstorm hung over the town.

My uncle, who held a high position in the town council, foresaw disaster.

He sent my aunt and his daughters away to his chateau, and advised me

to go with them. But I felt that I could not go away without having seen

Madame Lola again, and having collected my goods from her.

"On the day on which I went to her at last, the disturbance in the

streets was so great that I had to approach her abode by a network of

little side streets, and even that was extremely difficult. But upon entering

the house I found it, from doorway to garret, one seething mass of armed

people streaming in and out, the whole place indeed like a witch's cauldron.

There was no time to talk of bonnets. She herself, standing on the counter,

discoursing and directing the people, at the sight of me jumped straight

into my arms. 'Ah,' she cried, 'your heart has driven you the right way

at last!' And the whole crowd, she with it, at this moment advanced out

of the house and down the street. It dragged me with it, or I was so filled

with the very enthusiasm of the woman that I went freely. In this way,

in a second, I was whirled into a barricade fight, and on to the barricades,

always at the side of Madame Lola.

"She was loading the guns and handing them to the combatants, and

she was using for the terrible task all the verve and adroitness which

she had used in trimming her bonnets. Now all the people around her, although

they were brave, were afraid, and had reason to be so; but she was not

in the least afraid. As she handed the rifles to the men on the barricade,

she handed them with the weapons some of her own fearlessness. I saw this

on their faces. And it was strange that I myself was at the time convinced

that nothing could harm her, or could harm me as long as I was with her.

I remembered our old cook at Coburg telling me that a cat has nine lives.

Madame Lola, I thought, must have in her the life of nine cats. At that

moment I really saw her as something more than human, although she was,

as I think I told you, no lady of noble birth, but only a milliner of

Lucerne, not young.

"It was then that I myself, carried away by the rage around me, seized

a rifle and fired into the crowd of soldiers and town militia which was

slowly advancing up the street against us. My own uncle De Watteville,

for all I knew, might be leading them, but I had no thought for him. At

the same moment I was struck down, I know not how, and dropped like dead.

"When I woke up I was in a small room, in bed, and Madame Lola was

in the room with me. As I tried to move I found that my right leg was

all done up in bandages. She gave a great exclamation of joy at seeing

me awake, but then approached with her finger on her lips. In the darkened

room she told me of how the fight was over, and how I had killed the chaplain

of the Bishop of St. Gallen. She begged me to be very still, first because

my leg had been broken by a shot, and secondly, because things were still

upset in Lucerne. I was in great danger and must be kept a secret in her

house.

"I was there in the garret of her house, for three weeks, being nursed

by her. The fighting was still going on, and I heard shots. But of this,

of my wound, of what I had done and what my people would say, even of

my dangerous position, I hardly thought. It seemed to me that I had, somehow,

got up very high outside the world in which I used to live, and that I

was now quite alone there, with her. A doctor came to see me from time

to time. Nobody else came, but Lola would put on her shawl and leave me

for a while, begging me to keep very quiet till she came back. These hours

when she was away were to me infinitely long.

"But while I was with her we talked together much. When I have since

thought of it, I remember that she did not say a great deal, but that

I myself talked as well as I have always wished to do. Altogether, I understood

life and the world, myself and God even, while I was in the garret. In

particular we talked of the great things which I was to do in life. I

had, you understand, already done enough to be known amongst people, but

both of us felt that this was only the beginning.

"I understood that many of her friends had left Lucerne, and that

she was exposing herself to dangers for my sake, and I begged her to go

away. No, she said, she would not leave me for anything in the world.

First of all, after what I had done, the revolutionists of Lucerne looked

upon me as a brother, and would all be ready to die foi my sake. But more

than that, she explained, blushing deeply, in case we were found by the

tyrants of the town or their militia, she and I must both insist that

we had taken no part in the fight, but were here together because of a

love affair. She would have to pose as my mistress, and I as her lover,

while my wound would be said to have been given me by a jealous rival.

These words of hers, although the whole thing was only a comedy, again

made me feel extraordinarily happy, and made me dream of what I would

do when I got well again. Yes, I do not know if any real love affair could

possibly have made me as happy.

"At last one evening she told me that the doctor had declared me

to be out of danger, and that we must part. She was leaving Lucerne herself

that night. I was to go away, secretly, in the early morning. A friend,

she said, would place his carriage at my disposal, and himself escort

me out of town. A sort of terror came over me at her words. But I was

too slow. I did not know what was the matter with me till it was too late.

Madame Lola went on talking gently to me. I was, she said, to have something

Nobody else came, but Lola would put on her shawl and leave me for a while,

begging me to keep very quiet till she came back. These hours when she

was away were to me infinitely long.

"But while I was with her we talked together much. When I have since

thought of it, I remember that she did not say a great deal, but that

I myself talked as well as I have always wished to do. Altogether, I understood

life and the world, myself and God even, while I was in the garret. In

particular we talked of the great things which I was to do in life. I

had, you understand, already done enough to be known amongst people, but

both of us felt that this was only the beginning.

"I understood that many of her friends had left Lucerne, and that

she was exposing herself to dangers for my sake, and I begged her to go

away. No, she said, she would not leave me for anything in the world.

First of all, after what I had done, the revolutionists of Lucerne looked

upon me as a brother, and would all be ready to die foi my sake. But more

than that, she explained, blushing deeply, in case we were found by the

tyrants of the town or their militia, she and I must both insist that

we had taken no part in the fight, but were here together because of a

love affair. She would have to pose as my mistress, and I as her lover,

while my wound would be said to have been given me by a jealous rival.

These words of hers, although the whole thing was only a comedy, again

made me feel extraordinarily happy, and made me dream of what I would

do when I got well again. Yes, I do not know if any real love affair could

possibly have made me as happy.

"At last one evening she told me that the doctor had declared me

to be out of danger, and that we must part. She was leaving Lucerne herself

that night. I was to go away, secretly, in the early morning. A friend,

she said, would place his carriage at my disposal, and himself escort

me out of town. A sort of terror came over me at her words. But I was

too slow. I did not know what was the matter with me till it was too late.

Madame Lola went on talking gently to me. I was, she said, to have something

for my trouble, and she would give me all the bonnets that she had in

her shop. 'For I myself,' she said, 'am not coming back to Lucerne.' So

with the assistance of her little maid she made the journey up and down

the stairs twelve times, each time loaded with bandboxes, which she placed

around me. I began to laugh, and in the end could not stop again, for

I found myself nearly drowned in bonnets of all the colors of the rainbow,

trimmed with flowers, ribbons, and plumes. The floor, the bed, chair,

and table were covered with them, probably the prettiest bonnets in all

the world.

'Now,' she said, when she had filled the room with them, 'here you have

the wherewithal to conquer the hearts of women.' She herself put on a

plain bonnet and shawl, and took my hand. 'Do not ever,' said she, 'bear

me any grudge. I have tried to do you good.' She put her arms around my

neck, kissed me, and was gone. 'Lola!' I cried, and sank back in my chair

in a faint. I passed, when I woke up, a terrible night. There was not

a single pleasant thing for me to think of. The image of the curate of

the Bishop of St. Gallen also began to worry me, and it seemed to me that

I had nothing to turn to in all the world.

"Lola was as good as her word. The next morning an elderly Jewish

gentleman, of great elegance, presented himself in my garret, and at the

foot of the stair I found his handsome carriage waiting for me. He drove

me through the town, where here and there I still saw traces of the fighting,

and entertained me pleasantly on the way. As we were nearing the outskirts

of the city he said to me: 'The Baron de Watteville's carriage will meet

us at such and such a park. But the feelings of Monsieur your Uncle have

been hurt by your behavior, and he has charged me to say that he prefers

you to continue your journey straight on, so that he and you should not

meet until later.'

"'But does my uncle,' I exclaimed in great surprise, 'know of what

has happened to me?'

" 'Yes,' said the old Jew, 'he has indeed known all the time. The

Baron has much influence with the clergy of Lucerne, and it is doubtful

whether we could have done without him.' He said no more, so we drove

on in silence, I in a disturbed mind.

"My uncle's carriage was indeed waiting near a park, as the Jew had

said. As we stopped, a man got out of it and slowly came up to meet us,

and I recognized the red-haired young man whom I had seen in Lola's house

on my first visit there, and later, I now remembered, on the barricade.

He now looked as if he had gone through much. He limped when he walked,

and his face was very pale and stern as he bowed to my companion. Still,

as he looked around at me, he suddenly smiled. 'So this,' I heard him

say, 'is Madame Lola's little caged goldfinch?'

"'Yes,' said the old Jew, smiling, 'that is her golem.'

"Then I did not know what I found out later, that the word golem,

in the Jewish language, means a big figure of clay, into which life is

magically blown, most frequently for the accomplishment of some crime

which the magician dares not undertake himself. These golems are imagined

to be very big and strong.

"The two saw me into my uncle's carriage, and we took leave of one

another. I drove on, but I had too much to think of now, and I did not

know where to find myself again. The smell of gunpowder of the barricades,

our talks of God and Lola's kiss in the attic, together with all these

bonnets which she had given me, all ran before my eyes, like the colored

spots which you see before your eyes when you have for a long time been

looking at the sun, I have not been able, since then, to think much of

those great deeds which I was to perform. I cannot even remember what

they were. But still, I have killed the curate of the Bishop of St. Gallen,

and I must be careful until I get out of this country. I have seen a doctor,

who tells me that my leg has been so skillfully put together that it is

as if it had never been broken."

"And so you are," I said, "trying to find this woman, and

searching for her everywhere, lying awake at night?"

"You guess that?" said Pilot. "Yes, I am looking for her.

I do not know what to think or feel about anything until I shall see her

again. Still she was not young, you know, and no woman of noble birth,

but only a milliner of Lucerne."

Now I had heard Pilot's tale. And while I had been listening to it, I

had been frightened more than once. There were many things in it alarming

to my ears. I thought, I have not been drunk a single time since I lost

Olalla, till tonight. It is obvious that when I drink now, even as much

as two bottles of this Swiss wine, my head betrays me. That comes from

thinking, for a long time, of one single thing only. This tale of my friend's

is too much like a dream of my own. There is much in his woman of the

barricades which recalls to me the manner of my courtesan of Rome, and

when, in the middle of his story, an old Jew appears like a djinn of the

lamp, it is quite clear that I am a little off my head. How far can I

be, I wonder, from plain lunacy?

To clear up this question I went on drinking.

The Baron Guildenstern, during the course of Pilot's narration, had from

time to time looked at me with a smile, and sometimes winked at me. But

as it drew on he had lost his interest in it, and had had a new bottle

brought in. Now he opened it, and refilled the glasses.

"My good Fritz," he said, laughing, "I know that ladies

love their bonnets. A husband to them means a person who will buy them

bonnets of all possible shapes and colors, God bless him. But it is a

poor article of dress to get off a woman. I have let them keep the bonnet

on after everything else had gone; and as to having it flung at your head,

I prefer the chemise."

"Have you never, then, paid your court to a woman without getting

the chemise?" Pilot asked, a little nervously, looking straight in

front of him at things far away.

The Baron watched him attentively, as if he were on the point of finding

out that a failure and an unsatisfied appetite might have a value for

some kinds of people. "My dear friend," he said, "I will

tell you an adventure of mine in return for your confession":

"Seven years ago I was sent by the colonel of my regiment in Stockholm,

the Prince Oscar, to the riding school of Saumur. I did not stay my term

out there, as I got into some sort of trouble at Saumur, but while I was

there I had some pleasant hours in the company of two rich young friends

of mine, one of whom was Waldemar Nat-og-Dag, who had come with me from

Sweden. The other was the Belgian Baron Clootz, who belonged to the new

nobility, and possessed a large fortune.

"Through letters of introduction of old aunts of ours, my Swedish

friend and I dropped for a time into a curious community of old ruined

Legitimists of the highest aristocracy, who had lost all that they had

in the French Revolution, and who lived in a small provincial town near

Saumur.

"They were all of them very aged, for when they had been young the

ladies had had no dowries to marry on, and the gende-men no money to maintain

a family in the style of their old names, so there had been no younger

generation produced. They could thus foresee the near end of all their

world, and with them to be young was synonymous with being of the second-best

circles. The ladies held their heads together over my aunts' letters,

wondering at the strangeness of conditions in Sweden, where the nobility

still had the courage to breed.

"It all bored me to death. It was like being put on a shelf with

a lot of bottles of old wine and old pickle pots, sealed and bound with

parchment.

"In these circles there was much talk of a rich young woman who had

for a year been renting a pretty country house outside the town. I had

seen it myself, within its walled gardens, on my morning rides. In the

beginning she interested me as little as possible. I thought her only

one more of the company of Beguines. I wondered, though, how it was that

the qualities of youth and prosperity were in her no faults, but on the

contrary seemed to endear her to all the dry old hearts of the town.

"They themselves eagerly furnished me the explanation, informing

me that this lady had consecrated her life to the memory of General Zumala

Carregui, who had been, I believe, a hero and a martyr to the cause of

the rightful king of Spain, and had been killed by the rebels. In his

honor she dressed forever in white, lived on lenten food and water, and

every year undertook a pilgrim's voyage to his tomb in Spain. She gave

much charity to the poor, and kept a school for the children of the village,

and a hospital. From time to time she also had visions and heard voices,

probably the sweet and martial voice of General Zumala. For all this she

was highly thought of. That she had, before his death, stood in a more

earthly relation to the martyr in no way damaged her reputation. The collection

of old maids of both sexes were on the contrary much intrigued by the

idea of experience in this holy person, as were, very likely, the eleven

thousand martyrized virgins of Cologne when they were, in paradise, introduced

to the highly ranking saint of heaven, St. Mary of Magdala.

"But the heart of my friend Waldemar, when he met her, melted as

quickly as a lump of sugar in a cup of hot coffee.

" 'Arvid,' he said to me, 'I have never met such a woman, and I know

that it was the will of fate that I should meet her. For as you know my

name is Night-and-Day, and my arms two-parted in black and white. Therefore

she is meant for me—or I for her. For this Madame Rosalba has in

her more life than any person I have ever met. She is a saint of the first

magnitude, and she uses in being a saint as much vigor as a commander

in storming a citadel. She sits like a fresh, full flower in the circle

of old dry perisperms. She is a swan in the lake of life everlasting.

That is the white half of my shield. And at the same time there is death

about her somewhere, and that is the black half of the Nat-og-Dag arms.

This I can only explain to you by a metaphor, which presented itself to

me as I was looking at her.

"

'We have heard much of wine growing since we came here, and have learned,

too, how, to obtain perfection in the special white wine of this district,

they leave the grapes on the vines longer than for other wines. In this

way they dry up a litde, become over-ripe and very sweet. Furthermore,

they develop a peculiar condition which is called in French pourriture

noble, and in German, Edelfaule, and which gives the flavor to the wine.

In the atmosphere of Rosalba, Arvid, there is a flavor which there is

about no other woman. It may be the true odor of sanctity, or it may be

the noble putrefaction, the royal corrodent rust of a strong and rare

wine. Or, Arvid, my friend, it may be both, in a soul two-parted white

and black, a Nat-og-Dag soul.'

"On the following Sunday—in May, it was—I managed to be

introduced to Madame Rosalba, after mass, at dinner in the house of an

old friend of mine.

"These old aristocrats, in the midst of their ruin, kept a fairly

good table, and did not despise a bottle of wine. But the younger woman

ate lentils and dry bread, with a glass of water, and did this with such

a sweet and frank demureness that the diet seemed very noble, and nobody

would have thought of offering her anything else. After dinner, in the

fresh, darkened salon, she entertained the company, with the same frankness

and modesty, by describing a vision which she had lately had. She had

found herself, she said, in a vast flowery meadow, with a great flock

of young children, each of whom had around its head a small halo, as clear

as the flame of a little candle. St. Joseph himself had come to her there,

to inform her that this was paradise, and that she was to act as nurse

to the children. These, he explained, were none other than those first

of all martyrs, the babes of Bethlehem murdered by Herod. He pointed out

to her what a sweet task was hers, inasmuch as, just as the Lord had suffered

and died in the stead of humanity, so had these children suffered and

died in the stead of the Lord. A great felicity had at his words come